Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to present #DigitalInvasions’ (#invasionidigitali), a project which has just finished its second edition, held on 24 April to 4 May 2014. Digital Invasions’ is an Italian bottom-up project of collective participation in creation and sharing of cultural contents in order to enhance and promote Italian cultural heritage, through the use of web and social media. This project is an example of new forms of a democratic, participatory and inclusive digital culture.

Prosumers and new ways of cultural heritage dissemination through UGC

Democratization of data and information, in the web 2.0 and social media era has allowed creation of a participatory knowledge that, mainly by using interconnection, social sharing and co-creation of content and cultural value, made it possible to exploit network’s potential.

This change of perspective was already heavily supported also by the European Union since its Dynamic Action Plan guidelines for the EU co-ordination of digitisation of cultural and scientific content (DAP 2005) on issues concerning users and content:

“Users need to benefit more from the networking of cultural knowledge, as the implementation of technologies enables the development of a European Cultural information space. They need to be facilitated to find easily and use cultural content and to contribute their own knowledge and experience, becoming active citizens in information societies”.

Also focusing on specific Key issues such as:

• Engaging audiences in re-use and content production;

• Mobilising cultural institutions to make best use of existing technologies to enable digital access by all citizens.

During the Web 1.0 phase, web was presented as an one-way, passive, static and anonymous medium, in which, according to scholars, “the online experience was more like the reading of a book than the sharing of a conversation” [Kozinets 2010a].

With the Web 2.0 phase, web has transformed in a participatory platform, shared, fluid and personalized. With a wide opening to the users’ contributions, even information and cognitive system has been literally transfigured, from a top-down, one-to-many and content-centered system to a bottom-up, many-to-many and user-centered one.

In this system, user self-generates digital containts – different from those produced by traditional media – defined user-generated contents (UGC), exponentially contributing to decentralization and democrati- zation, according to information openness model. According to this model, in fact, to create and manage the content and the information are no longer, or not just, the centralized authorities (experts, etc.), but various and disseminated stakeholders: users, contributors, prosumers etc. [Ciappei et al. 2010; Bonacini 2011; Bonacini 2012], able to interact easily with new mass digital technologies. In this 2.0 phase, user consuming culture has turned into a prosumer or a consumer who participates in a new kind of production defined prosumption [Bruns 2008].

The real Web 2.0 revolution lies on the role of user who has acquired knowledge, technical expertise and ability to interact with this platform. Nowaday, social and economic development of our modern society depends on this new awareness and capacity. Exponential evolution of digital content creation has led to a real cultural revolution, where ICTs have become increasingly dominant. Evolving from a mass consumption society, our society has been transformed definetively in a mass cultural production society – also defined software society, whose cultural output is what Lee Manovich calls software culture [Manovich 2011; Manovich 2013] – where UGC have become so abundant to talk about a “cornucopia of online consumer data” [Kozinets 2010b] and cul- tural production takes on aspects of mass collaboration (an emblematic model is Wikipedia).

So, we live in a digital culture, where bottom-up and top-down processes are simultaneous and users contribute in a variety of ways and in the meanwhile they are consuming information [Uzelac 2008]. Our culture economic model, based on a broad diversity and plurality of information and perspectives, is defined networked information economy [Benkler 2006]. In our mass production society and in its networked information economy, acting as prosumers of cul- tural contents, users act as providers of knowledge, exploiting simultaneously the social and participatory modes of internet communication, as a kind of socialcasting [Bennato 2011], whose distribution process refers to a community of people who decide autonomously to increase the contents’ circulation thanks to sharing opportunities offered by new technology and participative web platforms, with a strong cultural and symbolic matrix, since that flow of content occurs with the cooperation of people who enjoy the same content.

In our software culture, there are specific cultural processes (creating, distributing, receiving and sharing both information and knowledge), which are mediated by specific digital tools, software or applications, enabling prosumers to create, share and disseminate their cultural contents. According to Matarasso [2010], this process changes the way of thinking about culture and partecipation:

“The coining of the term ‘prosumer’ marks a growing recognition, not just that people can be both cultural producers and consumers (something that has always been the case) but also that conventional ideas about professionals and amateurs are increasingly meaningless. As museums and other cultural institutions open up curatorial and programming process to forms of co-creation, the knowledge of pro- fessionals is being modified by the experience and insights of their audiences”.

Communication in a digital context is more fragile than appears. Process requires sender and receiver using compatible technologies which evolve quickly, differently and continuously. Moreover, it re- quires them to boast a similar mindset or the ability, the wisdom, the will to deeply understand each other. Which may prove difficult when we come to Cultural Heritage that is, by nature, highly intangible and thus leaves room for extremely personal ‘interpretations’.

If, on one side, those interpretations may appear distant and of no real value for defining the specific cultural object they refer to, on the other side they represent an invaluable asset to better define that very cultural object and deeply understand the way it is perceived by the audience.

Engaging the audience in a closer relationship with the Cultural Heritage they are surrounded by may prove effective to co-create additional cultural value. Initiatives aimed at that can enable:

• A better understanding of the communication issues affecting Cultural Heritage;

• An increased awareness of the needs and difficulties related to the protection and valorization of Cultural Heritage;

• a sense of ‘participation’, so to actively maintain and enhance the value of any cultural experience. Digital media constitutes a challenge not only for museums communicating art, history, cultural heritage, but for all the staff of cultural institutions, organizations and businesses. The challenge, for museums, is to change their museums praxis re-inventing themselves “in order to embrace a prosumer culture” [Schick 2010].

Today, production of cultural content is really easy thanks to social and geo-social networking platforms and their use in mobility. In addition, the real-time sharing of a place, an object or a live moment, has a huge evocative and communicative potential, because authenticity, emotion, excitement and satisfaction are expressed in a non-filtered way and give this communication an unparalled effectiveness [Milano 2011], fostering forms of digital sociality. The amazing spread of social media (participatory by nature) and digital tools like smartphones and tablets makes this challenge increasingly inviting and lead us all to inevitably rethink communication altogether. The open-endedness of those media explain the possibilities for a two-ways communication processes and for the creation of a kind of content that is not merely ‘user-centered’ or ‘user-driven’ but, rather, fully ‘user-generated’ also at a Cultural Heritage level.

#DigitalInvasions: best practice of crowd cultural value co-creation

#DigitalInvations project (#invasionidigitali) is a strong and wide example of user involvement both in cultural value co-creation and content sharing of suitable to Cultural Heritage enhancement [Marianna Marcucci et al. 2014; Bonacini 2014]. This bottom-up initiative is unique in its kind, both for the consistency and virality of this phenomenon, and for its novelty and its direct and indirect effects on Italian cultural communication. At the base of #DigitalInvations’ great success are, of course, the profound change which has occurred in users’ role and the desire to share and partecipate cultural value, fostered by social platforms spread.

#DigitalInvations are ‘social media mobs’ of people who support Italy’s museums and cultural heritage by ‘invading’ them and then doc- umenting their cultural experience on blogs and social media. In this way, people can raise awareness, interest, curiosity around cultural sites and generate positive response from a wider audience and, potentially, investors.

This project is all about co-creating and nurture cultural value through proactive participation of visitors into the museums’ communication life-cycle. It is characterized by a fully bottom-up approach, where people organize independently single events all around the coun- try during a given time frame. Each ‘invasion’ is meant to create new forms of conversation about arts and culture, and to transform Italy’s heritage into something that is open, welcoming and innovative. Social and digital communication are key to the invasions: ‘invaders’ are bloggers, archeology amateurs, artists, photographers, Instagrammers, historians, communication experts, but also common people with the most varied backgrounds, united by a shared desire to promote their cultural heritage with social media. All of them boast a real passion for their country and its unique heritage, and own well established social media accounts. Inspired by a contingency, #DigitalInvations aims now to become a sort of ‘national territorial lab’ for new social and digital communication products and models, and a tool to enhance both visitor’s experience and museum/cultural site performance.

#DigitalInvations were immediately recognized as a best practice in transmedium approach applied to national heritage and its integrated ways of promotion, a kind of urban gaming useful to provide a different and collectively built vision of cultural places and objects, giving them a new life [Symbola 2013].

Manifesto

In every country, the very own artistic and cultural heritage represents a great resource. To allow this heritage to express its potential, it is needed to embrace innovation and grasp the profound changes taking place in modern society. While a conservative trend still pervades the management of culture, in many international contexts a process of change has been started, which goes hand in hand with the evolution of society and its technological progress.

The acceleration of the digital revolution can contribute to renovate the cultural institutions and promote a concept of ‘open and widespread’ cultural heritage. A radical change is happening, especially thanks to those new forms of socialization and interaction with the new digital and social platforms on the web. Through them, knowledge and participation of the users are encouraged at all levels, increasing and customizing the appeal of the cultural offer and, most of all, activating new interaction mechanisms of fruition and comparison of the cultural offer.

For these reasons:

1. We believe that the application of the new forms of communication and shared multimedia to the cultural heritage is a fundamental opportunity to boost the transformation of the cultural institutions into open platforms for the circulation, exchange and production of value, capable of ensuring an active communication with the public, and the fruition of cultural heritage free of geographic boundaries wherein the sharing and the model of open access will be the best formulas.

2. We believe in the new forms of conversation and circulation of the artistic heritage, no more authoritarian and conservative but open, free, friendly and innovative.

3. We believe in a new relationship between museums and visitors based on participation, creation and promotion of culture.

4. We believe that the platforms connecting visitors, experts, scholars and enthusiasts, allow users to cooperate by offering museums their UGC personal content (User Generated Content) that may encourage co-creative cultural values.

5. We believe in new experiences of visiting cultural sites, no longer passive but active, where knowledge is not only transmitted but also built, where the visitor is involved and able to produce himself forms of art.

6. We believe that internet and social media are a great opportunity for cultural communication, a way to involve new players, shoot down all kinds of barriers and further facilitate the creation, sharing, dissemination and use of our artistic heritage.

7. We believe that internet is able to trigger new ways of management, conservation, protection, communication and exploitation of our resources.

#DigitalInvasions2013: born of a massive digital phenomenon and its Manifesto

Designed by Fabrizio Todisco, the very first edition of #DigitalInvasions was held on April 20-28, 2013 as a sort of bottom up-Culture Week in a crowded mode (Culture Week 2013 edition was, in fact, abolished by Italian Ministry of Culture for financial reasons) and based on use of smartphones, tablets, tags and social networks. #DigitalInvations has been able to grow across the country thanks to a network of people and partners, including #igersitalia (Italian Instagramers), Digital Natives, #iofacciorete (travel bloggers), Officina Turistica and National Associa- tion of Small Museums.

By actively working together, it was decided to create the website www.invasionidigitali.it, to write and promote its Manifesto, repro- duced in full in the next page, that might help to further understand motivations that lie behind this format.

www.invasionidigitali.it website, with its brand on high-impact posters, its slogan with main hashtags #invasionidigitali, #liberiamo- lacultura (#letsfreeculture) and #laculturasiamonoi (#weareculture), its profiles on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, Foursquare, Google+ and Flickr, was officially launched on 2 April 2013. At the very beginning, museums and institutions allowing a digital invasions inside were only 5.

From April 2 to 18, accessions have grown at a phenomenal rate and moltiplications of these local initiatives was viewable on website’s Google map, on which every single digital invasion was updated and geolocated by the staff, reaching in a very short time a total of over 300 invasions organized in all Italian regions. In this way, a mass parteci- patory and shared platform has been created, unique in the world, in which everyone – from the common art lover to cultural institutions – thanks to social media activities, helped to undermine the hierarchic and still plastered Italian word of culture and its communication.

As a blogger wrote when invasions increased progressively on Google map, Italy looked like a sick, sprinkled with red blisters, infected by a virtual virus, that is spreading fast, and all those blisters looked like Garibaldi’ scarlet shirts, ready to march on Italy, but they were coming in peace.

Each #plannedinvasion (#invasioneprogrammata) was a mini-digital-social event in itself: every coordinator created invasion’s event on Facebook or Eventbrite with its own poster (according to specific editorial guidelines), indicated to participants (invaders) the official event hashtag and any procedures for sharing photos and video on different social platforms.

Website automatically aggregated any post and digital content with official tags. Invaders were also invited to take a photo of their digital invasion concluded and to create short videos to upload on Youtube. From all videos collected (sixteen in total), the staff made a unique video on #digitalinvasions2013, as a bottom-up promotional video on cultural and touristic beauties of Italy, made by Italian people.

Data from #DigitalInvasions2013

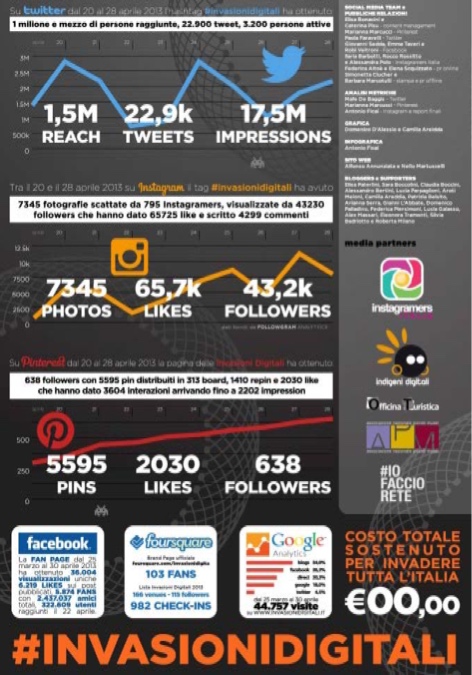

At the very end, every coordinator was invited to fill in a short report to collect final data on #digitalinvasions. Those data were highlighted through an infographic, we are going to analyze.

Final reports collected were 225 (91 historical centers, 21 archaeological sites, 86 museums and 27 naturalistic parks); weekend April 27-28 was the most liked for organizing #digitalinvasions. 225 invasions were carried out by 9.434 invaders, for a total of 10.798 artworks, objects and sites photographed and shared on the web. Analytics provided data were measurable only for those social networks in which it was possible to quantify hashtag #invasionidigitali (use of hashtags on Facebook came on June 12, 2013).

With 3.200 people active on Twitter, in the week 20-28 of April, were produced 22.900 tweets with and reached over 1.500.000 people.

On Instagram, 795 people have taken 7.345 photos, which were viewed by 43.230 followers, getting 665.725 likes and 4.299 comments.

The page on Pinterest, with 313 board, had 638 followers who have pinned 5.595 images, repinned 1.410 times, with 2.030 likes, 3.604 interactions and 2.202 impressions.

List of venues on Foursquare (166) had 115 followers and 982 check-in.

Facebook fan page, from March 25 to April 30, has got 36.004 views, 5.874 fans (with a total of 2.437.037 friends, 322.609 of which achieved only during 22 April), 6.219 likes on published posts.

www.invasionidigitali.it website in the same period got 44.757 visits.

Indirect results achieved by the Facebook Fan Page and Twitter profile demonstrate the viral potential of such an operation, which can rightly be considered a form of crowded-digital-marketing for culture, whose idea of virtual network has been beautifully rendered by a mul- timedia painting specially designed by the artist Fabrice de Nola to celebrate the achievements of the project.

#DigitalInvasions2014: a massive digital phenomenon from Italy to the world

After first edition’s success, in the following months, #DigitalInvasions’ staff has joined a number of institutional initiatives related to promotion of cultural heritage through social media (‘White Digital Night’ for Museums’ Night on July 13 and again on December 13; Researchers’ Night on September 27; European Heritage Day on September 28-29).

The project was also presented at the Digital Heritage Conference in Marseilles in October, at the National Conference of Small Museums in Assisi, at Mediterranean Borsa of Archaeological Tourism in Paestum, at the Imaginary Festival in Perugia in November and at the BTO Buy Tourism Online Conference in Florence in December. In April 2014, the project has been just presented – through a workshop and a planned invasion in the Museum of Baltimora – at the Museum and the Web Conference 2014 in Baltimore.

New website www.invasionidigitali.it has been launched on March 14, 2014, also available in English.

Over 400 #DigitalInvasions, were held from April 24 to May 4.

Baltimore’s digital invasion has pioneered this project beyond national borders. On the “old European continent” invasions were recorded in Germany (the Platform, along the Isar River and Valentin Karlstadt Musäum of Monaco; the Landesmuseum Natur und Mensch in Oldenburg; the Filarmonik Orkestra and the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin), Denmark (Kulturcentret Assistens in Copen- hagen), in Bosnia and Herzegovina (History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo).

Overseas, two invasions were carried out in Australia (Museum of Contemporary Art and The Lucy Osburn/Nightingale Foundation Museum in Sydney) and Brazil (Museu do Arte do Rio in Rio de Janeiro).

A digital ‘virtual’ invasion has just been promoted by the organizers of International Museum Day which take their guests on a virtual tour through three of the biggest online image archives from the field of art, culture and history, such as Europeana, Prometheus and Artigo, and in- vite them posting and sharing images and selected artworks and telling stories and informations about them. Followers could participate on Twitter and on Facebook asking questions, or just interacting following the hashtags online.

The second edition has just ended and the staff is collecting final reports so we aren’t be able to give more ‘numbers’ about it, but it apperas reasonable to consider that probably more than 15,000 people have been involved.

Cultural policies and socio-digital impacts of #DigitalInvasions projects

In times of economic turndown, when budget cuts heavily affect cul- tural management policies and strategies, the use of digital data, infor- mation and value co-created by (and with) the audience may generate an environment in which it contributes in:

• mitigating losses of socially valuable asset;

• optimizing (and minimizing, too, in a longer term) costs of communication;

• generating new added-value content by re-use and re- interpretation of pre-existing content. #DigitalInvasions’ phenomenon couldn’t pass unnoticed on the national press and, in some cases, even on the international one, because of the huge ‘movement’ on a wide variety of social platforms. Each digital invasion organized in a museum, a library, an historic center, an archeological site or in a park, had extensive coverage on the local press, but the whole phenomenon of #DigitalInvasions gives an acceleration to crowd-social ways of cultural communication in Italy.

Impact of this project can be measured especially for indirect and deep implications in our society and especially in our cultural institutions that have suddenly had to deal with the numerous requests for clearances and access to video and photographic documentation.

Since the first edition #DigitalInvasions had the patronage from many municipal governments and from the Regional Department for Cultural Heritage and for Sicilian Identity (the only Regional Depart- ment to ensure its patronage of both editions).

To overcome legal issues and authorizations, video and photographs and their publishing and sharing on the web have been assimilated to a personal and non-commercial use (such as falling within the exemption provided by D.Lgs. no. 42/2004, art. 108, paragraph 3).

#DigitalInvasions are perceived, both by the institutions and citizens who have promoted and supported them, as an opportunity to highlight not only great museum collections or the most famous national historical centers, but especially those monumental, artistic and archaeological emergencies that make Italy a great heritage widespread and are worthy of a better conservation, enhancement and fruition.

Digital revolution, radically changing cultural consumption’s behaviors, requires our institutions to rethink not only forms of relationship with their audiences but, more important, models of distribution, enhancement, enjoyment and use of their cultural contents, in line with Europe for a more and more widespread and democratic dissemination of high-definition digital cultural contents, also requiring a broad rethinking of stringent copyright rules.

Italian Ministry of Culture, because of many national monuments, parks and museums joined the project, could not remain indifferent and gave a virtual ‘placet’ through the official profiles on Twitter and Facebook page; since the first edition it soon started sharing and retweeting posts and tweets of #DigitalInvasions.

Such a phenomenon opened the door, first, to a more conscious col- laboration with #DigitalInvasions’ staff, expressed by the organization of the Museum’s Night on May 18, 2013 in collaboration with IgersItalia and by the Ministry patronage for the first edition of the the White Digital Night on July 10, 2013.

Furthermore, #DigitalInvasions lead, without any doubt, to the full adoption of the participatory museum model and the full opening towards UGC to facilitate processes of co-creation and co-production of cultural value which can lead to new and innovative ways of cultural and creative consumption.

This happy and peaceful project showed that Italians don’t want anymore culture conceived by institutions as ‘property’ and ‘possession: #DigitalInvasions2013 has marked a point of no return in relationship with our cultural heritage. The proof is the recent request by the Super- intendence of Tuscany to authorize ‘selfies’ in front of Michelangelo’s David at the Accademia Gallery. The Twitter profile of Italian Minister of Culture and Tourism Dario Franceschini twitted remembering the last days of invasions during the second edition.

Are the invaders succeeding in liberalizing photos in Italian museums? We hope so.

PUBBLICATO IN: Proceedings of the First EAGLE International Conference – Europeana Eagle Project. Ed. www.editricesapienza.it

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benkler, Y. (2006). The Wealth of Networks: how social production trans- forms markets and freedom. London: Yale University Press (cit. on p. 267).

Bennato, D. (2011). Sociologia dei media digitali: relazioni sociali e processi comunicativi del web partecipativo. Roma: GLF editori Laterza. isbn: 9788842097716 (cit. on p. 267).

Bonacini, E. (2011). Il museo contemporaneo: fra tradizione, marketing e nuove tecnologie. Roma: Aracne. isbn: 9788854838314 (cit. on p. 266).

— (2012). “Il museo partecipativo sul web: forme di partecipazione dell’utente alla produzione culturale e alla creazione di valore culturale”. In: IL CAPITALE CULTURALE. Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage 5, pp. 93–125. url: http://riviste.unimc.it/index.php/cap-cult/article/view/201 (visited on 07/29/2014) (cit. on p. 266).

— (2014). Dal Web alla App. Fruizione e volorizzazione digitale attraverso le nuove tecnologie e i social media. Giuseppe Maimone Editore. isbn: 9788877513816. url: http://www.abebooks.co.uk/Web-App- Fruizione-volorizzazione-digitale-nuove/12535046430/bd (visited on 07/29/2014) (cit. on p. 269).

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and beyond: From production to produsage. Peter Lang (cit. on p. 266).

Ciappei, C. and M. Surchi (2010). Cultura. Economia & Marketing. Firenze University Press. isbn: 9788884535696 (cit. on p. 266).

Kozinets, R. V. (2010a). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Sage Publications (cit. on p. 266).

— (2010b). “Netnography: The marketer’s secret weapon”. In: Netbase Solutions, Inc. url: http://skitsol.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Netnography-Marketers-secret-weapon.pdf (visited on 07/29/2014) (cit. on p. 267).

Manovich, L. (2011). “Cultural software”. In: From new introduction to Software Takes Command manuscript. url: http://www.manovich.net/DOCS/Manoich.Cultural%5C_Software.2011.pdf (visited on 07/29/2014) (cit. on p. 267).

Manovich, L. (2013). Software takes command. A&C Black (cit. on p. 267).

Marianna Marcucci and F. Todisco (2014). “Invasioni Digitali at the Digital Heritage Conference in Marseille”. In: url: http://www. slideshare.net/AlbergoUniverso/marseille2013-27650454 (visited on 07/29/2014). Forthcoming (cit. on p. 269).

Matarasso (2010). Re-thinking Cultural Policy. Brussels: CWE Conference, Culture and the Policies of Change, pp. 66–76. url: http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/cultureheritage/cwe/Rethink%5C_EN.pdf (cit. on p. 267).

Milano, R. (2011). “Come il Web sta cambiando il marketing turistico”. In: Viaggi in rete. Dal nuovo marketing turistico ai viaggi nei mondi virtuali. Ed. by R. Gerosa and R. Milano. FrancoAngeli, pp. 59–71. isbn: 9788856867015 (cit. on p. 268).

Schick, L. (2010). “Can you be Friends with an art Museum? rethinking the art Museum through Facebook”. In: Papers presented at the confer- ence in Tartu, 14-16 April 2010. Ed. by A. Aljas et al. url: https://xa. yimg.com/kq/groups/20447737/1520697127/name/Culture+in+ the+digital+age+-+Tartu+Conferance.pdf%5C#page=36 (visited on 07/29/2014) (cit. on p. 268).

Symbola (2013). Io sono cultura. L’Italia della qualità e della bellezza sfida la crisi. Unioncamere. url: http://www.symbola.net/assets/files/ Io%20Sono%20Cultura%202013-WEB%5C_1373367079.pdf (cit. on p. 270).

Uzelac, A. (2008). “How to understand digital culture: Digital Culture a resource for a knowledge society?” In: Uzelac, A. and B. Cv- jetičanin. Digital Culture: The Changing Dynamics, Institute for International Relations. Culturelink Joint Publications 15. Zagreb: Institut za mèd junarodne odnose, pp. 7–21 (cit. on p. 267).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the important contributions provided by our regional ambassadors and tecnical staff, for their co- operation which help us in completion of the “Invasioni Digitali” project.

In addition we would like to thank all the International invaders for their great support in organizing the invasions outside of Italy especially in Germany but also in Australia, USA, Denmark, Bosnia, Brasil.

In addition we would like to thank the italian Small Museums association.

Co-Authors: Elisa Bonacini, Marianna Marcucci, Fabrizio Todisco